Corpus based methods for nonverbal communication

The following was prepared for: Research methods in Linguistics: Multidisciplinary approaches. University of Madeira, Portugal

In the Lebenswelt of everyday communication, it is the combination of fluid verbal and nonverbal semiosis that creates meaning. While many insights can be gained from textual discourse analysis, the nuances and richness of human communication comes to the fore when it is an integrated whole that includes nonverbals. If phenomenological experience doesn’t lead one to this conclusion, it is also supported by quantitative studies suggesting two-thirds of human communication is nonverbal (Burgoon et al., 2016).

The importance of nonverbals is supported by research in cognitive sciences suggesting:

- Human cognition is mostly (some research has claimed 98%) unconscious and is inseparable from emotion. Moreover, cognition is embodied, meaning ideas, language, and even thought are mediated by the body (Lakoff, 2010).

- Human needs, emotions, and intentions are processed by the limbic brain. Nonverbal communication, in particular body language is, to a large extent, the expression of unconscious limbic processing (Lamendella, 1977). Gestures are expressions of embodied cognition (Kinsbourne, 2006).

- In contrast to largely unconscious nonverbal communication, verbal language is more consciously driven and concentrated in the frontal lobe of the brain, which is responsible for thinking, planning, and judgment.

Nonverbals often occur without our conscious awareness and, thus, are explicable in terms of the limbic system. Involuntary facial expressions, for instance, originate in the subcortical areas of the brain (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2013). There is also evidence that head movements encode emotional intent (Livingstone & Palmer, 2016).

This paper introduces corpus based methods for nonverbal communication in three main sections. The first ‘Multimodal Corpora’ summarizes some existing corpus-based approaches and studies. ‘Interpretation’ discusses interpretation of nonverbals within discourse analysis. The ‘Example’ section outlines how nonverbal analysis was integrated into a domain specific discourse analysis of natural resource debates. This is a discussion paper and is not meant to be a comprehensive summary.

Multimodal corpora

Multimodal approaches to discourse studies have emerged from the recognition that the lexical level of language is “just one among the many resources for making meaning” (Kress, 2011: 38). Multimodal corpora draw from the lexical as well as aural, linguistic, spatial, and visual capacities or modes (Murray, 2013). Beyond texts, multimodal data is obtained from a range of media such as audio, video, and images. Foster & Oberlander’s (2008) definition emphasizes audio-visual recording by defining a multimodal corpus as:

an annotated collection of coordinated content on communication channels such as speech, gaze, hand gesture, and body language, [that] is generally based on recorded human behaviour (4).

In addition to the data itself (i.e., recorded human behaviour), annotation of the multimodal corpus is a defining feature.

Existing Corpora

As Knight indicates in a 2011 review article, many multimodal corpora have been limited to specific, mono-lingual, specialist domains within a given discourse context. For instance, several corpora simulate meeting room environments often in controlled experimental conditions with specialized audio-visual equipment. These include:

- MM4 Audio-Visual Corpus (McCowan et al., 2003)

- NIST Meeting Room Phase II Corpus (Garofolo et al., 2004)

- AMI corpus (Carletta et al., 2005) which consists of 100 hours of meetings

- VACE Multimodal Meeting Corpus (Chen et al., 2006)

- MSC1 (Mana et al., 2007)

More recent corpora cover a wider variety of data, subjects, and collection techniques. Examples include:

- Rovereto Emotion and Cooperation Corpus (RECC) (Cavicchio & Poesio, 2012) which uses psycho-physiological indexes (heart rate and galvanic skin conductance).

- Lima et al.’s (2013) corpus of nonverbal vocalizations including 121 sounds representing positive and negative emotion categories.

- MMCOIC, Multimodal Corpus of Intercultural Communication (Lin, 2017): 24 h of recorded conversations.

- ViMELF (2018): a small corpus of 20 dyadic video-mediated conversations in an informal setting between previously unacquainted participants from Germany, Spain, Italy, Finland and Bulgaria, (using English).

The table below lists some multimodal corpora (expanding on Knight’s 2011 summary).

| Corpus / Reference | Description |

|---|---|

| AMI Meeting Corpus (Carletta et al., 2005) | Multi-modal data set consisting of 100 hours of meeting recordings<br>https://groups.inf.ed.ac.uk/ami/corpus/ |

| CID (Corpus d'interactions dialogales / Corpus of Interactional Data) (Bertrand et al., 2008) | 8-hour audio-video corpus in French aiming at multimodal annotation which includes phonetics, prosody, morphology, syntax, discourse and gesture studies. https://www.ortolang.fr/market/corpora/sldr000027 |

| CUBE-G corpus (Rehm et al., 2008) | Cross-cultural corpus of dyadic conversations. German, Japanese<br>https://hcai.eu/projects/cube-g/ |

| Czech Audio-Visual Speech Corpus for Recognition with Impaired Conditions (Železný et al., 2006) | 20 hours of audio-visual records of 50 speakers in laboratory conditions. Czech.<br>https://catalogue.elra.info/en-us/repository/browse/ELRA-S0284/ |

| D64 (Oertel et al., 2013) | 4-5 people recorded over two 4 hour sessions. Non-directed, spontaneous conversations in an apartment room. Participants wore markers to track movement |

| Fruit Cart Corpus (Aist et al., 2012) | 104 videos of 13 participants. 400 utterances total. Designed for research is dialogue systems |

| Göteborg Spoken Language Corpus (GSLC) (Jens Allwood et al., 2000) | A 1.2 million word corpus, some of which has been aligned with video records. Conversations from different social contexts.<br>https://data.flov.gu.se/gslc/ |

| IFADV Corpus (Van Son et al., 2008) | 20 dialog conversations of 15 minutes we recorded and annotated, in total 5 hours of speech. Dutch.<br>https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/IFA-SpokenLanguageCorpora/IFADVcorpus/ |

| MIBL Corpus (Wolf & Bugmann, 2006) | Dialogues between a person who already knows a card game (teacher) and another person who doesn’t know the card game. Links speech to movement (used to train service robots) |

| Mission Survival Corpus 1 (MSC 1) (Mana et al., 2007) | Corpus of short meetings with up to 6 participants in each. Most of the meetings cover predetermined topics and are scripted. |

| MM4 Audio-Visual Corpus (McCowan et al., 2003) | 29 short meetings between 4 people on controlled, experimental conditions. |

| The NIST Meeting Room Pilot Corpus (Garofolo et al., 2004) | Pilot corpus of 15 hours of meetings in a laboratory. 19<br>meetings/15 hours recorded between 2001 and 2003. |

| NMMC (Nottingham Multimodal Corpus) (Knight et al., 2006) | 250,000 words video and audio recorded, consisting of single speaker lectures and dyadic academic supervisions. |

| The<br>Bielefeld Speech and Gesture Alignment Corpus (SaGA) (Lücking et al., 2010) | 280 minutes, 25 dialogs of interlocutors engaging in a spatial communication task. |

| SmartKom Multimodal Corpus (Schiel et al., 2002) | HCI based. 96 single users recorded across 172 sessions. Users carry out prompted tasks recorded in public spaces. |

| SmartWeb Multimodal Interaction Corpus (Schiel & Mögele, 2008) | 99 recordings of human-human-machine dialogue. |

| UTEP-ICT Cross-Cultural Multiparty Multimodal Dialog Corpus (Herrera et al., 2010) | 200 minutes. Task based conversations between groups of 4 participants in a room. |

| VACE Multimodal Meeting Corpus (Chen et al., 2006) | Recordings of meetings based on wargame scenarios and military exercises. 3D body tracking of participants. |

| Rovereto Emotion and Cooperation Corpus (RECC) (Cavicchio & Poesio, 2012) | Uses psycho-physiological indexes (heart rate and galvanic skin conductance) |

| Corpus of nonverbal vocalizations (Lima et al., 2013) | Corpus of nonverbal vocalizations including 121 sounds representing positive and negative emotion categories |

| MMCOIC, Multimodal Corpus of Intercultural Communication (Lin, 2017) | 24 h of recorded conversations |

| ViMELF (2018) | A small corpus of 20 dyadic video-mediated conversations in an informal setting between previously unacquainted participants from Germany, Spain, Italy, Finland and Bulgaria, (using English). |

Annotation

Annotation is a challenge for multimodal corpus research given both the time it requires as well as the lack of annotation standards (Abuczki & Ghazaleh, 2013). Brunner & Diemer (2021) note that artificial intelligence supported annotation does not (yet) provide a satisfactory solution (65).

We can generally distinguish between:

- Annotation of video files. For example, the MUMIN coding scheme (J Allwood et al., 2005).

- Annotation of NVE elements as part of a lexical transcription corpus (e.g., Jefferson, 2004).

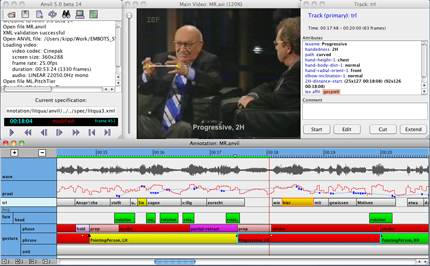

For video annotation, perhaps the most common tool is Anvil (Michael Kipp, 2001; Michael Kipp et al., 2006). Knight (2011), mentions some multimodal corpora projects use other tools (summarized in table below).

| Tool | Source | Link |

| Anvil | (Michael Kipp, 2001; Michael Kipp et al., 2006) | http://www.dfki.de/~kipp/anvil/ |

| DRS | (University of Nottingham, 2011) | http://sourceforge.net/projects/thedrs/ |

| ELAN | (Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, 2022) | http://www.lat-mpi.eu/ |

| EXMARaLDA | (Schmidt & Wörner, 2014) | https://exmaralda.org/en/ |

Given that multimodal information and research topics are often too varied and rich to annotate in its entirety, the annotation scheme will often reflect targeted research questions. MUMIN coding scheme, for instance, was designed for the studying gestures and facial displays in interpersonal communication, and has a focus on annotations relating to feedback, turn management and sequencing (J Allwood et al., 2005). To accommodate researchers in different fields to focus on features of interest, Brunner et al. (2017) advocate a layered annotation approach. An example is the Corpus of Academic Spoken English (CASE) annotation method which uses separate but parallel files for:

- Transcription layer

- XML layer

- Orthographic layer

- Part-of-speech (POS) tagged layer

Brunner & Diemer (2021) refer to the challenge researchers face in multimodal annotation as a “balancing act” between documenting nonverbal features and maintaining focus on those features that are “salient” in the context (64).

Interpreting Nonverbals

There are competing theories concerning the meaning and interpretation of nonverbal communication (NVC). Topics of debate include the extent to which nonverbal behaviours are universal by virtue of our common biological or evolutionary origins, or the degree to which they are culturally variable (Jack et al., 2012). Also debated is whether nonverbal behaviors are reflective of internal, cognitive states or whether they are better understood in terms of social interaction and influence (Crivelli & Fridlund, 2018).

As mentioned in the introduction, the importance of nonverbals is based on research suggesting that cognition is mostly unconscious, inseparable from the body, and expressed through embodied communication. It follows that nonverbals convey thoughts, feelings, and emotions in ways that speech alone does not. Nonverbals are often not inhibited and regulated in the same way as speech is, in the cortical and frontal lobe areas of the brain. Of course, this is a simplification. In reality, complex interactions occur between areas of the brain (Wood & Petriglieri, 2005). Nonetheless, the basic point is that the importance of nonverbals to discerning overall meaning is rooted in human cognition itself. Nonverbal communication is required to understand the full communicative intent, which encompasses emotions and reactions as well as thinking and judgment. While nonverbals can be deliberate and intentional, they often occur without our conscious awareness and, thus, are explicable in terms of the limbic system.

Another key point is that nonverbal communication is closely associated with the site of emotional processing, the limbic system. Emotions serve an important cognitive evolutionary function by allowing for rapid information processing with minimal deliberation (Tooby & Cosmides, 2008). It should be noted that there is not universal agreement that nonverbal communication is a reflection of internal emotions. With respect to facial expressions, Crivelli & Fridlund (2018) explain that, according to the behavioral ecology view of facial displays (BECV), facial displays are tools for social influence. The BECV contrasts with the basic emotions theory (BET), which holds that facial expressions reflect internal emotions.

The table below summarizes some nonverbal elements (NVE) with associated meanings, based on literature. It should be emphasized that these are instances mentioned in the contexts and cultures particular to the studies. Moreover, the elements area not exhaustive, but those observed in a specific case study (see Example section that follows).

| NVE | Meaning | Sources |

| Head tilt | Sign of interest, curiosity, and uncertainty | (H. Lewis, 2012) |

| eye gaze shifts upwards | Thinking (European-North American cultures) | (McCarthy et al., 2006) |

| Hand in ring shape | Precision | (Kendon, 2004) |

| Palm up | Uncertainty, emphasis, emotional helplessness, and social deference | (Givens, 2016) |

| Head shaking | Intensifier with thenegation carrying the meaning of ‘unbelievable’ | (McClave, 2000) |

| Iconic speech illustrators | Close relationship with the content of the speech | (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2012) |

| Metaphoric gestures | abstract ideas | (Beattie, 2016, 66). |

| Audible inhale/exhale | indicative ofagitation and emotional strain | (Poyatos, 2002) |

| Clenched fist | frustration, annoyance, or stress | (Phipps, 2012) |

| High blink frequency and duration | negative emotional states including stress and fear | (Haak et al., 2019) (Maffei & Angrilli, 2019) |

| “knit brow” | worry or concern | (Hartley & Karinch, 2017) |

| Shoulder shrug | innocence and helplessness | (Collett, 2003) |

Example

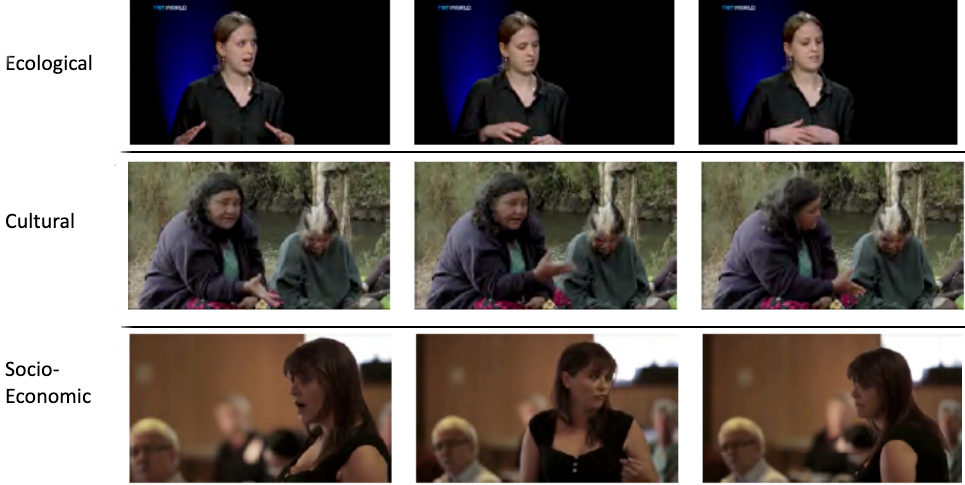

To integrate nonverbal analysis as part of a larger project related to intercultural communication and ecolinguistics (Frayne, 2021), I collected eight hours of audio and video recordings representing different perspectives on various mining operations and proposed developments. These included interviews, documentaries, recordings of ‘town hall’ type meetings. Timestamps of interest (points in the recording with distinctive and pronounced non-verbal expression) were then annotated and analyzed. Segments were categorized based on ecological, cultural, and socio-economic subject matter.

There were 25 files in total, each with a url associated back to the original audio/visual media. The transcripts included timestamps (e.g. 05:45). By looping through the transcripts and getting the last timestamp, the total runtime of the media was calculated as 7 hours 46 minutes. The average runtime was about 18 minutes.

Rather than annotating the entire corpus, selections were obtained using both top-down and bottom-up approaches. In the top-down approach, the media was watched/listened to manually, paying close attention to gesture, body language, or other non-verbal expressions. Timestamps of interest (i.e. points in the recording with distinctive and pronounced non-verbal expression) were then marked for further annotation. The bottom-up approach began by searching for keywords and phrases related to analytical themes (i.e., ecology, culture, socio-economic). Segments related to key themes were then identified for further analysis and annotation.

| Discourse Level | Description |

| Ecological | Discourse about nature and the more-than-human world; includes discourse that concerns ecology in a scientific sense, as well as human subjective experiences (Umwelten) |

| Cultural | Expressions of identity, values, and worldviews; people commenting about who they are, either directly orindirectly |

| Socio-Economic | Discourse related to economics, institutions, and power relations; aspects of social existence that do notexpress cultural identity |

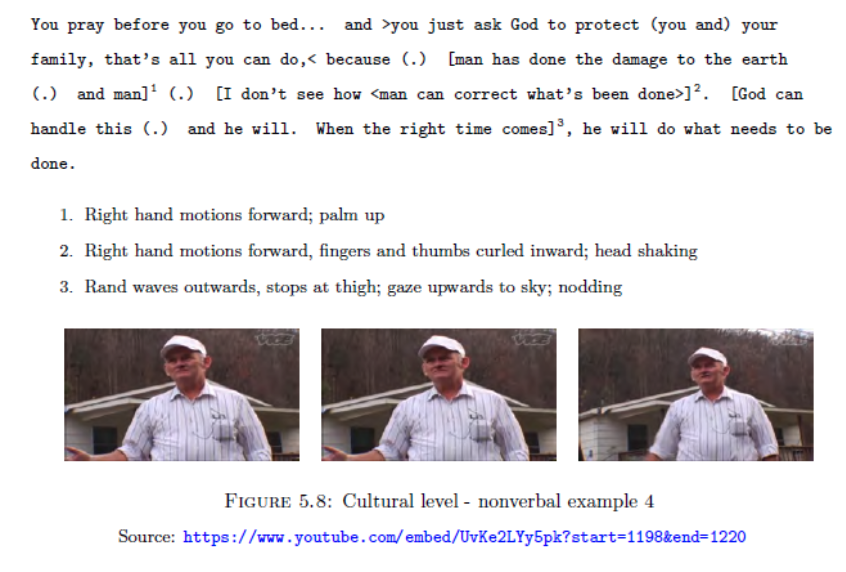

The annotation scheme was based on Gail Jefferson’s (2004), as adapted by (Beattie, 2016, 5). To improve readability footnotes were added to the transcription. Screenshots from frames were included with links to the original video clips.

The observed trends in facial expressions and gestures suggested that different cognitive responses were exhibited at different levels of discourse.

- The ecological level exhibited more verbal and spatial reasoning and did not appear to trigger emotional responses. In other words, the “fight or flight” emotional responses of limbic system and subcortical areas of the brain were being mediated. In contrast, speakers at the ecological level generally showed less facial expression. Gestures were predominantly iconic and depicted physical/spatial processes. Compared to the other levels of analysis, intonation and stress was less pronounced.

- Speakers at the cultural level displayed more power and confidence gestures, including pointing (to add emphasis), thumb displays, and fist pumping. Gestures were more metaphoric than was the case in the ecological level, depicting abstract concepts such as God, culture, identity, and fighting back. Contempt and agitation were displayed, at one point by a contempt expression (raised side of mouth) as well as the backwards thumb gesture on another occasion.

- The socio-economic level displayed a high degree of emotion, often expressed in the eyes. Universal facial expressions of fear and sadness could be seen in speakers and listeners. Gestures also indicated hopelessness and innocence, such as the palm open “pleading” gesture as well as shoulder shrugs.

Moving Forward

Nonverbal corpus methods have been used in empirical behavioural sciences as well as highly descriptive methods in pragmatics. Much recent research is driven by applications in human-computer interaction and artificial intelligence. What is perhaps lost in this focus is nonverbal analysis as humanistic inquiry. Interpretive, meaning-centred approaches can draw from the rich, embodied nature of human interaction to advance empathic understanding. Humanistic approaches with an ‘eye’ towards developments in AI and robotics could also help drive discussions on what is unique about human vs. machine cognition.

References

Abuczki, Á., & Ghazaleh, E. B. (2013). An overview of multimodal corpora, annotation tools and schemes. Argumentum 9, 9, 86–98.

Aist, G., Campana, E., Allen, J., Swift, M., & Tanenhaus, M. K. (2012). Fruit Carts: A Domain and Corpus for Research in Dialogue Systems and Psycholinguistics. Computational Linguistics, 38(3), 469–478. https://doi.org/10.1162/COLI_a_00114

Allwood, J, Cerrato, L., & Dybkjaer, L. (2005). The MUMIN multimodal coding scheme. Langage Resources and Evaluation, 273–287. http://www.ling.helsinki.fi/kit/2006k/clt310mmod/MUMIN-coding-scheme-V3.3.pdf

Allwood, Jens, Björnberg, M., Grönqvist, L., Ahlsen, E., & Ottesjö, C. (2000). The Spoken Language Corpus at the Department of Linguistics , Göteborg University. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(3). http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs/

Bertrand, R., Blache, P., Espesser, R., Ferré, G., Meunier, C., Priego-Valverde, B., & Rauzy, S. (2008). Le CID - Corpus of Interactional Data - Annotation et Exploitation Multimodale de Parole Conversationnelle. Traitement Automatique Des Langues, 49.

Brunner, M.-L., & Diemer, S. (2021). Multimodal meaning making: The annotation of nonverbal elements in multimodal corpus transcription. Research in Corpus Linguistics, 9(1), 63–88. https://doi.org/10.32714/ricl.09.01.05

Brunner, M.-L., Diemer, S., & Schmidt, S. (2017). “… okay so good luck with that ((laughing))?” – Managing rich data in a corpus of Skype conversations. Big and Rich Data in English Corpus Linguistics: Methods and Explorations, 19. https://varieng.helsinki.fi/series/volumes/19/brunner_diemer_schmidt/

Burgoon, J., Guerrero, L., & Floyd, K. (2016). Introduction to Nonverbal Communication. In Nonverbal communication (pp. 1–26). Routledge.

Carletta, Ashby, S., Bourban, S., & Mike Flynn Mael Guillemot Thomas Hain Jaroslav Kadlec Vasilis Karaiskos Wessel Kraaij Melissa Kronenthal Guillaume Lathoud Mike Lincoln Agnes Lisowska Iain McCowan Wilfried Post Dennis Reidsma Pierre Wellner, J. (2005). The AMI Meeting Corpus: A Pre-Announcement 1. www.idiap.ch

Cavicchio, F., & Poesio, M. (2012). The Rovereto Emotion and Cooperation Corpus: A new resource to investigate cooperation and emotions. Language Resources and Evaluation, 46(1), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-011-9163-y

Chen, L., Rose, R. T., Qiao, Y., Kimbara, I., Parrill, F., Welji, H., Han, T. X., Tu, J., Huang, Z., Harper, M., Quek, F., Xiong, Y., McNeill, D., Tuttle, R., & Huang, T. (2006). VACE multimodal meeting corpus. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 3869 LNCS(February), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/11677482_4

Collett, P. (2003). The Book of Tells: How to Read People’s Minds by Their Actions. HarperCollins Canada.

Crivelli, C., & Fridlund, A. J. (2018). Facial Displays Are Tools for Social Influence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.02.006

Foster, M. E., & Oberlander, J. (2008). Corpus-based generation of head and eyebrow motion for an embodied conversational agent. Language Resources and Evaluation ·, May. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-007-9055-3

Frayne, C. (2021). Language games and nature: a corpus based analysis of ecological discourse [Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg]. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:105-qucosa2-748562

Garofolo, J., Laprun, C., Michel, M., Stanford, V., & Tabassi, E. (2004). The NIST Meeting Room Pilot Corpus. https://tsapps.nist.gov/publication/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=150471

Givens, D. B. (2016). Reading palm-up signs: Neurosemiotic overview of a common hand gesture. In Semiotica (Vol. 2016, p. 235). https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2016-0053

Haak, M., Bos, S., Panic, S., & Rothkrantz, L. (2019). Detecting Stress Using Eye Blinks and Brain Activity from Eeg Signals.

Hartley, G., & Karinch, M. (2017). The Art of Body Talk: How to Decode Gestures, Mannerisms, and Other Non-Verbal Messages. Red Wheel/Weiser.

Herrera, D., Novick, D., Jan, D., & Traum, D. (2010). The UTEP-ICT cross-cultural multiparty multimodal dialog corpus. The Proceedings of the Workshop on Multimodal Corpora: Advances in Capturing, Coding and Analyzing Multimodality, 49–54.

Jack, R. E., Garrod, O. G. B., Yu, H., Caldara, R., & Schyns, P. G. (2012). Facial expressions of emotion are not culturally universal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(19), 7241 LP – 7244. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1200155109

Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of Transcript Symbols with An Introduction. In Pragmatics and Beyond New Series (Vol. 125, pp. 13–31). https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.125.02jef

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge University Press.

Kinsbourne, M. (2006). Gestures as embodied cognition: A neurodevelopmental interpretation. Gesture, 6(2), 205–214.

Kipp, Michael. (2001). ANVIL A generic annotation tool for multimodal dialogue. EUROSPEECH 2001 - SCANDINAVIA - 7th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology, 1367–1370. https://doi.org/10.21437/eurospeech.2001-354

Kipp, Michael, Neff, M., & Albrecht, I. (2006). An Annotation Scheme for Conversational Gestures: How to economically capture timing and form. Proceedings of the Workshop on Multimodal Corpora (LREC’06)., 24–27.

Knight, D. (2011). The future of multimodal corpora. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 11(2), 391–415. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1984-63982011000200006

Knight, D., Bayoumi, S., Mills, S., & Crabtree, A. (2006). Beyond the Text : Construction and Analysis of Multi-Modal Linguistic Corpora. 2nd International Conference on E- Social Science.

Kress, G. (2011). Multimodal discourse analysis. In J. P. Gee & M. Handford (Eds.), Routledge handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 35–50). Routledge.

Lakoff, G. (2010). Why it Matters How We Frame the Environment. Environmental Communication, 4(1), 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524030903529749

Lamendella, J. T. (1977). The Limbic System in Human Communication (pp. 157–222). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-746303-2.50010-5

Lewis, H. (2012). Body Language: A Guide for Professionals. SAGE Publications.

Lima, C. F., Castro, S. L., & Scott, S. K. (2013). When voices get emotional: A corpus of nonverbal vocalizations for research on emotion processing. Behavior Research Methods, 45(4), 1234–1245. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0324-3

Lin, Y. L. (2017). Co-occurrence of speech and gestures: A multimodal corpus linguistic approach to intercultural interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 117, 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.06.014

Livingstone, S., & Palmer, C. (2016). Head Movements Encode Emotions During Speech and Song. In Emotion (Vol. 16). https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000106

Lücking, A., Bergmann, K., Hahn, F., Kopp, S., & Rieser, H. (2010). The Bielefeld Speech and Gesture Alignment Corpus (SaGA). In M Kipp, J.-P. Martin, P. Paggio, & D. Heylen (Eds.), LREC 2010 Workshop: Multimodal Corpora–Advances in Capturing, Coding and Analyzing Multimodality (pp. 92–98).

Maffei, A., & Angrilli, A. (2019). Spontaneous blink rate as an index of attention and emotion during film clips viewing. In Physiology & Behavior (Vol. 204). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.02.037

Mana, N., Lepri, B., Chippendale, P., Cappelletti, A., Pianesi, F., Svaizer, P., & Zancanaro, M. (2007). Multimodal Corpus of Multi-Party Meetings for Automatic Social Behavior Analysis and Personality Traits Detection. Proceedings of the 2007 Workshop on Tagging, Mining and Retrieval of Human Related Activity Information, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1145/1330588.1330590

Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H. C. (2012). Culture and nonverbal communication. In M. L. Knapp & J. A. Hall (Eds.), Nonverbal Communication. De Gruyter.

Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H. S. (2013). Facial Expressions. In D. Matsumoto, M. G. Frank, & H. S. Hwang (Eds.), Nonverbal Communication: Science and Applications. Sage.

McCarthy, A., Lee, K., Itakura, S., & Muir, D. W. (2006). Cultural Display Rules Drive Eye Gaze During Thinking. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37(6), 717–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106292079

McClave, E. Z. (2000). Linguistic functions of head movements in the context of speech. Journal of Pragmatics, 32(7), 855–878. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00079-X

McCowan, I., Bengio, S., Gatica-Perez, D., Lathoud, G., Monay, F., Moore, D., Wellner, P., & Bourlard, H. (2003). Modeling human interaction in meetings. ICASSP, IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing - Proceedings, 4, 748–751. https://doi.org/10.1109/icassp.2003.1202751

Murray, J. (2013). Composing Multimodality. In C. Lutkewitte (Ed.), Multimodal Composition: A Critical Sourcebook. Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. (2022). ELAN (Version 6.4). The Language Archive. https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan

Oertel, C., Cummins, F., Edlund, J., Wagner, P., & Campbell, N. (2013). D64: A corpus of richly recorded conversational interaction. Journal on Multimodal User Interfaces, 7(1–2), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12193-012-0108-6

Phipps, R. (2012). Body Language: It’s What You Don’t Say That Matters. John Wiley & Sons.

Poyatos, F. (2002). Nonverbal Communication Across Disciplines. John Benjamins Publishing.

Rehm, M., Nakano, Y., Lipi, A., Yamaoka, Y., & Huang, H.-H. (2008). Creating a standardized corpus of multimodal interactions for enculturating conversational interfaces.

Schiel, F., & Mögele, H. (2008). Talking and looking: The SmartWeb multimodal interaction corpus. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, LREC 2008, 1990–1994.

Schiel, F., Steininger, S., & Türk, U. (2002). The smartkom multimodal corpus at BAS. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, LREC 2002, 200–206.

Schmidt, T., & Wörner, K. (2014). EXMARaLDA. In Handbook on Corpus Phonology (pp. 402–419). Oxford University Press.

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2008). The Evolutionary Psychology of the Emotions and Their Relationship to Internal Regulatory Variables. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of Emotions (pp. 114–137). The Guilford Press. https://www.cep.ucsb.edu/papers/emotionIRVLewisCh8.pdf

University of Nottingham. (2011). Digital Replay System. https://thedrs.sourceforge.net/

Van Son, R. J. J. H., Wesseling, W., Sanders, E., & Van Den Heuvel, H. (2008). The IFADV corpus: A free dialog video corpus. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, LREC 2008, 2(1), 501–508.

ViMELF. (2018). Corpus of Video-Mediated English as a Lingua Franca Conversations. Trier University of Applied Sciences. http://umwelt-campus.de/case

Wolf, J. C., & Bugmann, G. (2006). Linking speech and gesture in multimodal instruction systems. Proceedings - IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, October, 141–144. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2006.314408

Wood, J. D., & Petriglieri, G. (2005). Transcending Polarization: Beyond Binary Thinking. Transactional Analysis Journal, 35(1), 31–39.

Železný, M., Krňoul, Z., Císař, P., & Matoušek, J. (2006). Design, implementation and evaluation of the Czech realistic audio-visual speech synthesis. Signal Processing, 86(12), 3657–3673. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sigpro.2006.02.039