William Morris and the digital age

Our current tech age is, in some ways, analogous to what previous generations faced with industrialization. Like the Industrial Revolution, narratives of progress through technology are met with labor upheavals, inequality, and alienation.

In the 19th Century, William Morris responded to the “dark Satanic Mills” of industrialization by calling for social reform and upholding the medieval idea of craft. To counter tech disenchantment in our own time, we can consider whether Morris’s legacy can inspire today’s digital economy.

From “The Californian Ideology” to Technofeudalism

When my generation came of age in the 1990s, a common narrative was that computing technologies would drive prosperity, break down old corporate and state power structures, and connect communities. Decades later, critiques of “dotcom neoliberalism” – or what Barbrook and Cameron referred to in their 1995 essay as “The Californian Ideology” – have a sympathetic ear.

There is growing evidence that public perceptions of the tech sector are souring. In a 2020 survey, two-thirds of Americans said social media has mostly a negative effect on society. A more recent study indicates that confidence in technology firms among the public is dropping. This despite an industry hype machine that pumps billions into convincing us that tech companies are paragons of progress. (Ad spend by Big Tech reached nearly $50 billion in 2021.)

The conventional argument that tech has led to increased prosperity is questionable. Networking and computing technologies that came largely from public research dollars have been monopolized by private firms, helping fuel historic levels of wealth inequality. Furthermore, there is growing evidence that investments in these technologies are not leading to increased productivity.

The idea that the knowledge economy would lead to more humane and fulfilling workplaces is also coming undone. Recent reports suggest toxic workplaces are the norm in tech.

The Industrial Revolution led to a system change from feudalism to capitalism. Some today, like Greek economist Yanis Varoufakis, argue that the global tech economy no longer qualifies as capitalism. Rather, he argues, we have transitioned to something better described as technofeudalism.

Morris and the ‘Arts and Crafts’ movement

The question is how to respond to such technological and economic forces. William Morris (1834–1896) is someone who addressed the economic paradigms of his day through advocacy, writing, and designing artifacts.

Morris was a British textile designer, artist, writer, and activist associated with the Arts and Crafts movement. Alongside contemporaries like John Ruskin, Morris developed a design ethos in response to the modern factory system, with its division of labor and the erosion of traditional crafts.

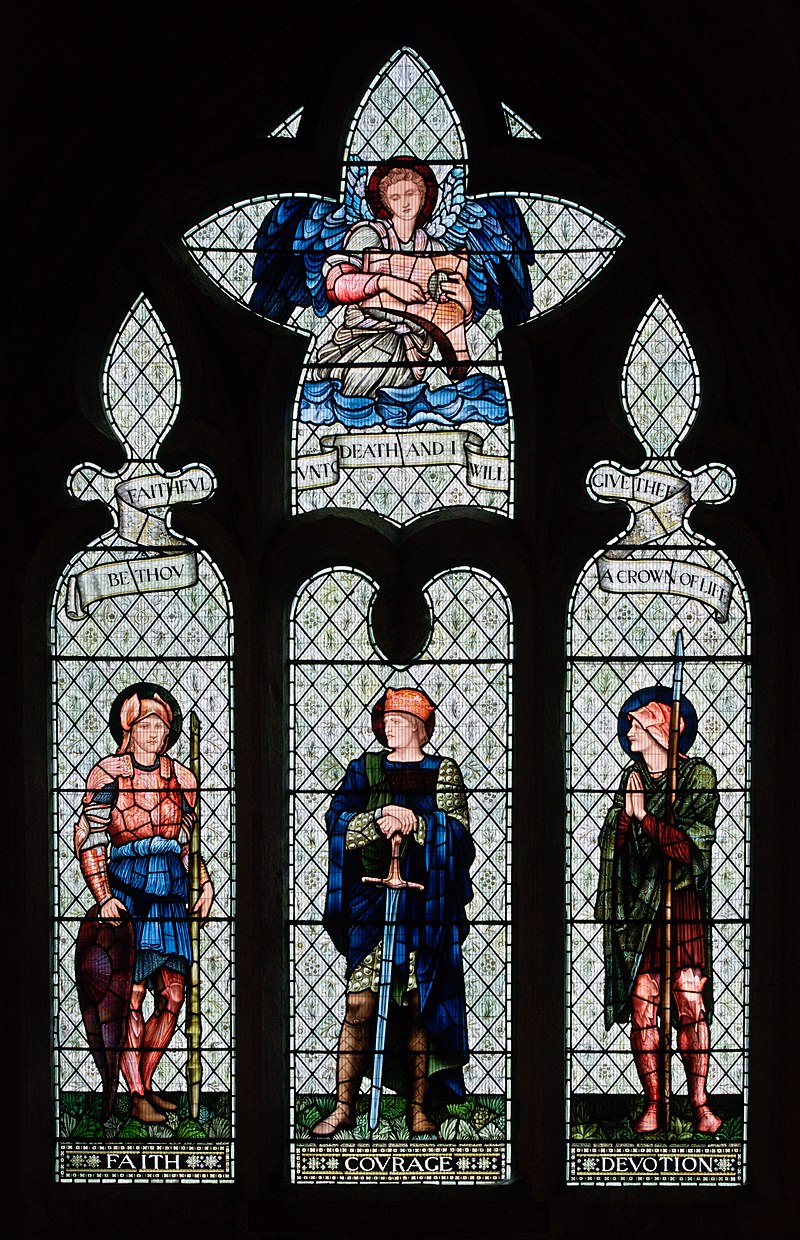

In 1861, Morris founded a company and began making furniture and decorative arts objects commercially. Patterns were based on flora and fauna, inspired by vernacular and rural traditions with an emphasis on affordability and anti-elitism. Products created by Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. included furniture, metalwork, stained glass, architectural carving and murals.

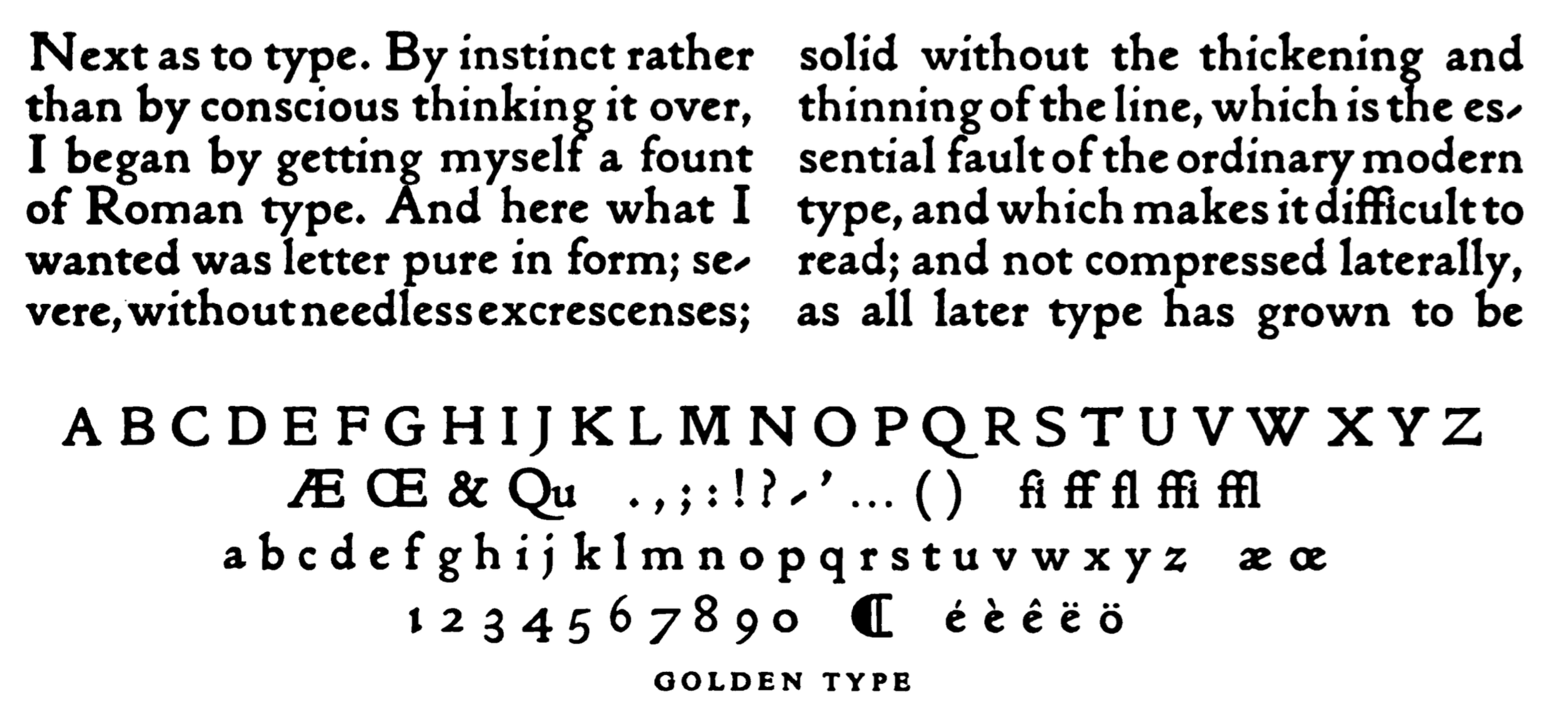

Later, in 1891 Morris founded the Kelmscott Press which produced works using traditional printing methods and hand-made paper. He also designed distinctive typefaces: Golden, Troy, and Chaucer.

Practitioners of the Arts and Crafts movement did not separate social reform from design reform. Morris sought to use art and design to help rebuild society based on the principles of simplicity and honesty. In contrast to the greed and exploitation of his age, Morris advocated for a more dignified and compassionate society.

Implications for the Digital Age

Followers in the Arts and Crafts movement drew parallels between mechanized production and broader socio-cultural issues of the time. Critiques were based on moral principles as well as the more basic conviction that the products and landscapes being produced were ugly and distasteful.

However, Morris and followers did not reject the technology, saying:

We do not reject the machine, we welcome it. But we would desire to see it mastered.

So too can we draw parallels between the computing revolution and malaise of our age. The effects of the tech industry on work, inequality, mental health, literacy, etc. are concerning, even dystopian. Notwithstanding the ecological impacts of materials and energy used by tech, much of the digital world is a form of virtual pollution or cultural junk. But this does not imply outright rejection of the technology.

Rather, like Arts and Crafts practitioners, one can go against the dominant industry trends, combine the old with the new, and strive to set a new standard. What this entails is an open question, but the following are some basic principles.

Quality over Money

The main purpose of a company should be to actually create something unique and quality. As Morris Biographer John William Mackail claimed:

Morris became a manufacturer not because he wished to make money, but because he wished to make the things he manufactured.

This contrasts with management priorities driven by financialization, where the product itself is often an afterthought.

Collaboration

In “A factory as it might be” Morris described his vision of a workplace as:

A group of people working in harmonious cooperation towards a useful end.

While this may seem self-evident, it’s a far cry from collaboration cultures found in many tech companies. Instead, it’s often people sitting by themselves at laptops not communicating. With the rise of bullshit jobs, many are not working towards any useful end at all.

Simplicity & Minimalism

Morris advocated for simplicity in terms of physical surroundings as well as lifestyle, saying in “The prospects of architecture in civilization”:

Simplicity of life, even the barest, is not a misery, but the very foundation of refinement.

The tech world is full of clutter and busy designs. I’ve often thought the internet would have been elegant if it were left as simple text, perhaps LaTeX, without ads and commercial ‘bells and whistles’.

Conclusion

As technological changes lead to social and economic uprooting, we would be naive to think that progress is linear. Morris and Arts and Crafts are examples that it is possible to uphold traditions, locality, and dignity in the face of economic steamrollers.